Visiting the battlefields of the Somme

Looking out over the beautiful French countryside – the tranquility broken only by birdsong and the distant sound of tractors bringing in the harvest – it’s almost impossible to imagine that a century ago, the Battle of the Somme was raging in these very fields. The first day, the 1st of July 1916, was the worst day in British military history, and the battle continued for five more months. It’s become pretty much the ultimate symbol of the futility of war: over a million people wounded or killed, and all for a gain of around six miles.

The trees and grass have, of course, grown back on the ravaged battlefields, the “torn fields of France” of which Isaac Rosenberg wrote; and in the pastoral scenes of the summer it’s hard even to visualise the hellish mud in which the soldiers laboured in the latter stages of the Battle of the Somme. But the battle has left enduring scars on the landscape – you just have to know where to look for them. In what must have been the most gargantuan clean-up operation, most of the trenches and shell craters were filled in by farmers returning to their land after the war, the Western Front leaving little more than the occasional chalky shadow in the ploughed fields. However, some areas (known as the Zone Rouge) remain completely off limits owing to the volume of unexploded shells, and there are even places where virtually nothing will grow because of the amount of poison in the soil. There are still places where one can glimpse what’s left of the Western Front, and after extensive research online and in the booklets they gave us at the airfield, I put together a day-long itinerary to enable us to see the main sites.

Albert and the Somme 1916 Museum

Our first port of call was the town of Albert, which suffered heavily in the First World War and was all but destroyed. Rebuilt after the war in Art Deco style, it’s now a pleasant little town with an impressive basilica.

Just to the right of the basilica is the entrance to the fascinating Somme 1916 Museum, which is a great place to start a tour of the Somme battlefields. It’s housed in a network of underground tunnels used as an air raid shelter during the Second World War, which adds to the atmosphere.

The museum tells the story of the Battle of the Somme through an introductory 3D film, archaeological exhibits, information boards and recreated scenes like this one, which give you a flavour of what life on the front line would have been like. I spotted a Dundee marmalade jar on the shelf, just like the ones we have at home.

The museum is the perfect way to brush up on the background to the Battle before you go out ‘into the field’ to see what’s left of the battlefield. I studied the First World War for GCSE History and then again in English Literature at A-level, and I found the museum a useful refresher.

The Newfoundland Memorial at Beaumont-Hamel

The Newfoundland Memorial at Beaumont-Hamel, not far from Albert, commemorates the terrible losses of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment on the first day of the Battle of the Somme. The Regiment lost 85% of its men within the first 20 minutes of the battle – around 660 men. Opened in 1925 (ironically enough by Field Marshall Haig, the very man who directed all these poor men to their deaths), it preserves the battlefield as it was left, complete with Allied and German trenches and the shell-cratered No Man’s Land in between. It’s run by Canadian students, who come over for a few months at a time to provide guided tours. On the day we visited, we noticed that the majority of our fellow visitors were British. Like the other First World War sites we went to, entry is free and it’s always open. It’s considered a sacred site, as it’s effectively also a cemetery because the remains of many soldiers still lie beneath the grassed-over battlefield. This site more than any of the others we visited brought home the brutal reality of the war.

The Caribou monument, by an English sculptor, is at the top of a small mound planted with Newfoundland-native plants, and you can walk up a winding path to the top to look out over the site. It lies behind the Allied front line, and you look out towards the German line.

You are able to walk through a short section of the Allied front line. The zigzag pattern of the front line trenches is because if the enemy managed to get into the trench, they would only be able to capture a small part of it. If it were a straight line, the enemy could shoot right the way along the trench and gain control of a much greater portion of it. It also meant that explosions or gas from shells couldn’t travel all the way along the trench.

The trenches would originally have been deeper than they are now, and of course they would have had dugouts where the men could shelter. I can’t imagine how exhausting it must have been to dig these – miles and miles and miles of them, multiplied by three for front line, support and reserve trenches, plus communications trenches linking them all.

What really got to me, seeing the trenches, was the fact that on the first day of the Battle of the Somme, the Allied soldiers believed that they had an easy job ahead of them. The German trenches had been extensively shelled in the week preceding the battle, and huge mines had been detonated just a minute or two before the start of the offensive, so they thought they’d simply go over the top and easily capture the German trenches. In fact, the Germans had dug down deep and were mostly safe in their concrete bunkers. The extensive shelling and mines alerted them to the fact that something big was about to happen. Not only that, but the shape of the land at Beaumont-Hamel gave the German gunners a huge advantage, as the Allied trenches were on higher ground than those of the Germans. That meant that the German gunners could clearly see the Newfoundlanders coming towards them, silhouetted against the skyline – an easy target.

I was astonished to see that in places, even the posts used to hold the barbed wire that was a brutal feature of No Man’s Land were still in situ. First World War barbed wire was considerably more vicious than the stuff we use today (you can see examples in the Somme 1916 Museum). The posts holding it were a clever corkscrew design so that they could be put into the ground silently. Apparently, local farmers returning to their land after the war took many of them and used them for their own fencing.

This is the so-called ‘Danger Tree’, supposedly the only surviving tree from the war. It was once part of a cluster of trees halfway into No Man’s Land at which the Newfoundlanders gathered during the battle, but it was also an easy landmark for the Germans and the casualties here were huge. I think this may actually be a replica, but it certainly calls to mind those black and white images of the stripped-bare trees destroyed by the battle.

The ground at Beaumont-Hamel is pock-marked with numerous craters, which don’t come out particularly well on camera.

There are a couple of cemeteries, too; this is the Y Ravine Cemetery, the name of which I’ll explain shortly.

Signs like these are commonplace on the former Somme battlefields. Tonnes of First World War munitions are dragged up by farming each year, many of which never detonated, so they’re really dangerous and still injure and kill people even a century later.

On our flight home a couple of days later, we made a detour to fly over Beaumont-Hamel to see the battlefield from the air. The aerial photos make it easier to make sense of the site. In this one, the caribou monument is in the top right-hand corner, and the lines of trenches are those of the Allies. It’s much easier to see from the air just see how many craters there are, and how many shells landed behind the main front line. You can also see the communications trenches running perpendicular to the front line, which enabled troops to get from one row of trenches to another.

You can clearly see the caribou sculpture in this (rather hazy) shot.

This photo shows the German front line, and behind it the natural ravine (known to the Allies as the ‘Y Ravine’ – hence the name of that cemetery), which the Germans fortified and used greatly to their advantage.

The next two images give a sense of how close the Allied and German front lines were to each other. The Allied trenches are to the right, and the German trenches to the left of these images.

You can also see how the surrounding land has recovered – you’d never think that it was the scene of such a bloody battle. That’s why I think it’s really good that the Canadians had the foresight to preserve this small part of the battlefield, and I can’t understand why the British and French don’t seem to have done the same. It’s a far better memorial to what happened than the gleaming marble monuments scattered across the otherwise pristine French countryside.

I should also point out that there’s an excellent museum at Beaumont-Hamel, which brings to life some of the individual stories of those who participated in the battle.

Thiepval Memorial

On the subject of grand memorials, our next stop after Beaumont-Hamel was the biggest of these: the Thiepval Memorial. There are many, many small cemeteries dotted around the countryside of the Somme. Far too many soldiers lost their lives for it to be practical to bring them all home, so they were laid to rest in small cemeteries like these, far from home, close to where they fell on the battlefield. Many of the graves simply read “Known unto God” because the remains were never identified.

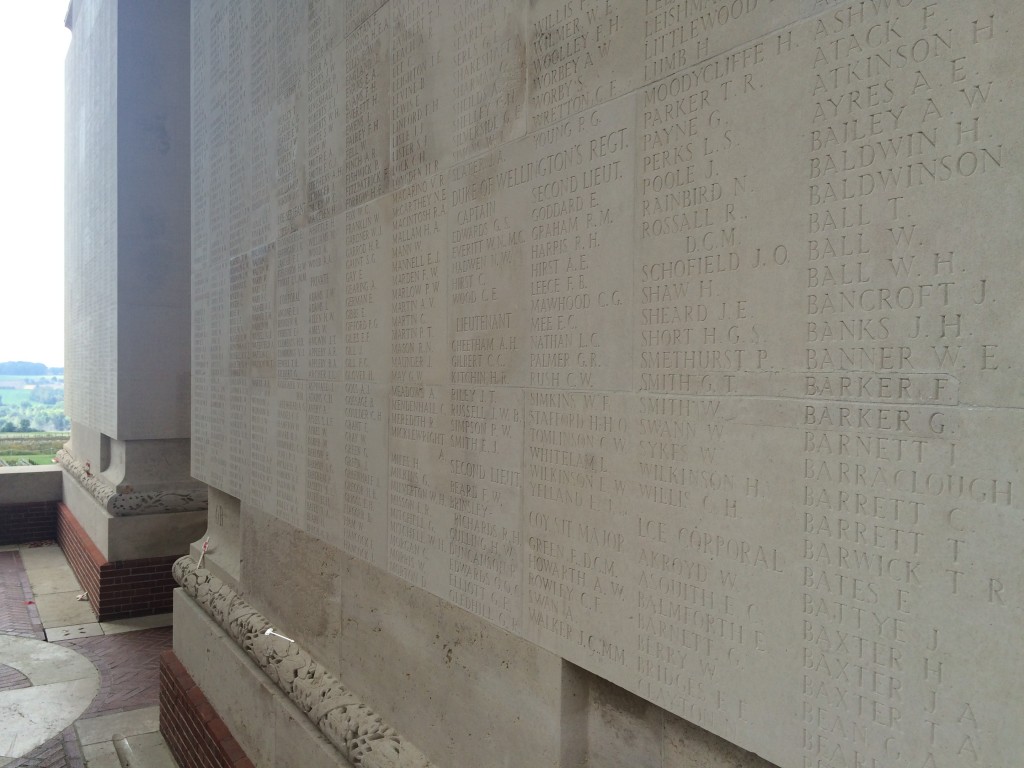

Tens of thousands more were never found, and the British-built monument at Thiepval is dedicated to them: the 72,246 men who went missing on the Somme battlefields between 1915 and 1918, who have no grave. Designed by British architect Sir Edwin Lutyens and opened in 1932, the ‘Monument to the Missing’ was built on one of the German army’s strongest sections of front line. There is also a cemetery here, containing 300 British (the white marble headstones to the left) and 300 French (the simple concrete crosses to the right).

All the sides of the base of the monument are absolutely covered in names, giving an impression of the scale of the losses. We spotted a few Ingrams, and wondered whether they were distant relatives.

The Lochnager Crater

I mentioned earlier that in the minutes before the start of the Battle of the Somme, the Allies detonated huge mines under the German lines. Our final stop of the day was to the Lochnager Crater, which was caused by one of those mines on the first morning of the Somme. The scale is overwhelming, and apparently the explosion – at the time the biggest ever man-made sound – could be heard as far away as London.

You can see the chalk under the grass; apparently the whole ground was white from the chalk brought up by the explosions. The bodies of many soldiers still lie here, the remains of one of whom was discovered as recently as 1998, identified by the name and service number etched into the razor found with his body.

The Battle of the Somme ended on the 18th November 1916, but of course the war dragged on for another two years after that. Although the Battle of the Somme entailed huge loss of life, it did nevertheless mark a sort of turning point in the war. Using the experience of this bloody battle, the Allies were able to modify their tactics for this new style of warfare, and many argue that the battle ultimately paved the way for Allied victory. Significantly, the Battle of the Somme also saw the first use of tanks, which terrified the Germans, who called them the “Devil’s chariots”; it was these that helped break the stalemate and gave the Allies a big advantage (by the end of the war, they had over 6,000 tanks, while the Germans only managed to produce 20, and then only in response to those of the Allies). Visiting the sites associated with the battle is an interesting and moving experience, and one that will make me look at the poppies on 11 November with even more empathy for the men who fought in that terrible war.

The day after that we visited Arras and another Canadian memorial there, which I’ll write about in another post.